by Laurie Pickard | Nov 23, 2014 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs, Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

Even though MOOCs don’t run on a semester schedule, I still like to think of my business education in those terms. As I near the end of the fall semester of my second year of self-made B-school, I’d like to reflect on some of the highlights of the past four months.

I talked to some very interesting people

I shared my thoughts on MOOC education with a grad student in Switzerland, answered some thought provoking questions from a startup in Bulgaria, and met a dynamic CEO who shared his insights on how employers see MOOC education.

I valued my coursework at over $50,000

I was recently asked how much my MBA coursework to date would have cost at a traditional university. Here’s my back of the napkin calculation: assuming $1000 per credit hour and 3 credit hours per course, I have racked up over $50,000 worth of free courses!

I facilitated a MOOC

Last year the State Department teamed up with Coursera to provide facilitated MOOC courses at embassies around the world as part of the MOOC Camp Initiative. In October and November of this year, I served as facilitator of one of these camps a the U.S. Embassy in Kigali, Rwanda. The course was “Beyond Silicon Valley: Entrepreneurship in Transitioning Economies” - perfect for the Rwandan context. I worked with an inspiring group of young Rwandan entrepreneurs, and even managed to arrange a Skype session with Professor Michael Goldberg.

A professor asked me to take his MOOC

One of the most exciting things that happened this semester was that a professor reached out to me and asked me to take his MOOC. And I’m glad he did! Professor George Siedel teaches an excellent course titled Successful Negotiation. Which brings me to my next highlight…

My best course assignment so far

The final assignment in Successful Negotiation is a negotiation exercise. The whole course builds up to this negotiation. Students in the course choose a negotiation partner, and each student is assigned one of two roles. The scenario was detailed enough that there was a lot to work with and plenty of opportunity to put the concepts in the course into practice. In addition to being a great practical assignment, it was a perfect solution to the problem of lack of student interaction in a MOOC. My only complaint about this course was that there was only one such negotiation. If more are included in a subsequent offering, I may end up taking this course again.

My most difficult course so far

Perhaps I shouldn’t speak too soon since I haven’t finished this course yet, but I am six weeks into Supply Chain and Logistics Management from MITx, and I am on track to pass. MIT courses are HARD. In many courses, a straight A is no big achievement, but in an MIT course, a 60% is a passing grade, and it’s difficult to get. This course has required me to reach back into the recesses of my memory to high school algebra and calculus, to dust off my college statistics, and to master Excel functions I didn’t even know existed. I sometimes feel like I did as a child taking piano lessons, when I would get so frustrated about a piece that I would end up practicing through tears until I finally got it. This course doesn’t make me cry, but it does sometimes test the limits of my determination. When I get that certificate of completion, I will feel very proud.

Next: winter term

I went to a college that had a winter term, during which students had time to do an intensive project or internship in between the fall and spring semesters. I’m taking a winter term this year to do a few practical business projects involving team work. First, I’m in a NovoEd course (co-presented with +Acumen) that involves financial modeling of a social enterprise and a substantial group work component. Second, I’m planning to do some group business games and simulations - more on that later. Finally, as treasurer of the employee association at the US Embassy in Kigali, I’m working on a restructuring of the Embassy’s commissary business. With these three group activities I’m planning to recreate at least part of the social learning component of a traditional degree.

by Laurie Pickard | Oct 17, 2014 | Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

I was recently interviewed by Niya Koleva of the Bulgarian website Smartigraphs. I enjoyed answering Niya’s questions so much that I wanted to re-publish the interview on my blog. Currently, most of Smartigraphs’ content is in Bulgarian - the site was started by a group of Bulgarian students - but they are planning to increase the amount of English language content published on the site. As Niya told me, “We started as a small team of students and have now expanded and have 5 authors and 2 designers working on various social topics ranging from energy to elections. Most of us have graduated or are currently enrolled in Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski, and only 2 people of the team are not studying Political science. We aim at explaining the world and complex concepts in a beautiful way through infographics. We are also working on an English version of the website so that one day a broader audience would be able to enjoy our work.” Below is the full interview, which originally appeared on Smartigraphs.

I was recently interviewed by Niya Koleva of the Bulgarian website Smartigraphs. I enjoyed answering Niya’s questions so much that I wanted to re-publish the interview on my blog. Currently, most of Smartigraphs’ content is in Bulgarian - the site was started by a group of Bulgarian students - but they are planning to increase the amount of English language content published on the site. As Niya told me, “We started as a small team of students and have now expanded and have 5 authors and 2 designers working on various social topics ranging from energy to elections. Most of us have graduated or are currently enrolled in Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski, and only 2 people of the team are not studying Political science. We aim at explaining the world and complex concepts in a beautiful way through infographics. We are also working on an English version of the website so that one day a broader audience would be able to enjoy our work.” Below is the full interview, which originally appeared on Smartigraphs.

As you might know most of us are political science students and some of us aspire to work in this field. You have a formal bachelor’s in Politics from Oberlin College. Can you tell us why you chose politics and how was your first degree different from your self-made no-pay-MBA?

When I entered university, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to study. I knew I had an interest in international themes, but I hadn’t had much exposure outside of the US. I thought I might study languages. Then I took a class on international relations, and it opened up this whole new world for me. It gave me a way of systematizing information on a grand scale, and I had the first inkling that it might actually be possible to understand the global big picture, at least through a certain lens. I appreciated the political science approach because it was rigorous and because it had some explanatory power beyond what studying language and culture was able to provide. I got a great education at Oberlin, and I emerged a much more well-rounded and thoughtful person. My No-Pay MBA has been a similarly mind-expanding experience, but it is more targeted. In this phase of my education, I am very focused on learning skills that will make me a better professional, whereas my undergraduate education (and even my graduate education to some extent) was about shaping my overall world view.

You have listed International Development, International Education, and Intercultural Communication as top skills on your Linkedin profile. Do you think your non-traditional educational path helps you further develop them? What other skills have you acquired through MOOCs?

I do see these skills as some of my most valuable, thought I’m not sure that my current educational pursuit is helping me to develop them. It’s more the reverse – my experience in international development, international education and intercultural communication make me a better student. Additionally, having an international focus – and taking MOOCs as an international student - allows me to see both the great potential and the challenges that this type of education faces.

As for new skills that I’ve learned, in addition to my ever-expanding repertoire of analytical tools (strategic/competitive analysis, financial analysis, operational/efficiency analysis), I am honing an entrepreneurial mindset and a way of looking at the world that is all about identifying opportunities. I seem to have a new business idea at least once a week.

As far as I know you speak Spanish and French. Do you think it is possible for people to learn a language online effectively? Have you tried to improve your language skills through courses or educational platforms online? I believe I once read on your blog that you like learning foreign languages, exotic ones for that matter.

You are correct that I speak both French and Spanish. I am also trying to learn Kinyarwanda, the local language of Rwanda – with strong emphasis on the word trying! I’ve never actually tried to learn a language online, other than to do vocabulary or grammar drills. The thing I love about learning languages is that they are a window on a culture. So without the cultural experience, a lot of the joy of learning a language is lost for me. However, I do think that online tools could be helpful for someone learning a language. For those with fairly advanced language skills, a MOOC in a subject area of interest could provide a great forum for enhancing language skills. I have plans to do this myself, in fact. A reader of my blog recently suggested a MOOC on project management that is only available in French.

You have worked in Nicaragua and Rwanda. Has your professional experience in these countries influenced your learning experience in any way?

Absolutely! I work on issues of economic growth, so my work typically involves taking a macro-perspective on development, at the level of a value chain, a sector, or an economy as a whole. One of the things I have loved about my work is getting to observe how a private sector is built and how an economy grows increasingly more complex. In a fast-growing economy like Rwanda’s you practically watch that happen in front of your eyes. With my business courses, I am getting a micro-level view of how individual enterprises operate. Between the two, I am building a very well-rounded picture of how business works. At heart I’m a geographer – that’s what my master’s degree is in. Geography as a social science is fundamentally about how we as human beings interact with our environment, and the forces of business are huge in shaping the world we have built. I find a lot of joy and fulfillment in trying to understand those forces and in trying to use them to lift people out of poverty.

You have shared on your blog that your main frustration with MOOCs are the Discussion boards/forums. Do you still feel anxious about them? Some educational specialists consider them to be the most fascinating part of MOOCs because they become the medium for intercultural dialogue and spread of ideas. After engaging in so many classes, what’s your standing on this?

Anxious wouldn’t be the word I would use; I would say frustrated – and yes, I do still feel frustrated with discussion forums. In a way they just seem outdated. Wouldn’t it be better if students could use video conferencing to have discussions in small groups, face to face? Or if you could have a real-time chat with someone about the ideas that come up in a course? Of course connectivity issues can make those things challenging, but I find the discussion board format very impersonal and unsatisfying.

Of course I love the idea of people being able to connect with one another and learn from one another around a shared interest. My problem is more with the disjointed feel of discussion forums and the clutter that results from mandatory posting requirements.

I know you supplement your MOOC curriculum with TED talks. Could you share with us your most favorite ones? For instance Top 5?

I do love TED talks. Below are some of my favorites.

Hans Rosling: Global population growth, box by box

Jill Bolte Taylor: My stroke of insight

Jason Fried: Why work doesn’t happen at work

Dan Palotta: The way we think about charity is dead wrong

Amy Cuddy: Your body language shapes who you are

by Laurie Pickard | Sep 20, 2014 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs, Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

What is the purpose of an MBA? I’m sorry to get all philosophical on you, but someone asked me the other day, and while I was able to rattle off a list of skills that I have learned since embarking on this journey (reading a balance sheet, calculating NPV, analyzing recurrent processes and finding inefficiencies,etc.), I wasn’t able to come up with an overarching statement of purpose regarding what an MBA is supposed to be or do.

The conversation left me thinking about whether an MBA is supposed to be management training, or whether it is more technical training. In trying to answer this question, I went back to an excellent article by Brooke Allen called ‘How to talk yourself out of getting an MBA.’ The article refers to a book called Managers, Not MBAs, which is also a great read. Both of these works set up the MBA as a management degree, then proceed to tear it down. As Henry Mintzberg, the author of Managers, Not MBAs says,

“It is time to recognize MBAs for what they are - or else close them down. They are specialized training in the functions of business, not general educating in the practice of managing. Using the classroom to help develop people already practicing management is a fine idea, but pretending to create managers out of people who have never managed is a sham.”

I suppose I agree with Mintzberg, and with Allen, that you can’t expect to learn how to be a manager from an MBA program. From what I’ve seen so far, getting an MBA is unlikely to make someone a good manager. But maybe that’s not a problem. I’m finding plenty of value in learning the “functions of business” and in learning to perform the types of analysis that are particular to business. In fact, maybe a better title for the degree than Master of Business Administration would be Master of Business Analysis.

But what if what you really want to learn is how to be a manager? If you can’t learn management in a business administration program - and frankly I agree with the two previously mentioned authors that if this is what you want to learn, then business school is probably not the place for you - where do you learn that skill set? I have four suggestions on where to start.

Managing yourself

I recently read a book called Business Without the Bulls%*t, in which the author starts the book by claiming that everyone is essentially a freelancer. What he means by this is that a good worker needs to manage him or herself - understand what is expected of you at work, and get things done well and on time without much oversight. The first place to learn management, then, is by managing oneself. You can find lots of great personal productivity tips on YouTube. Degreed.com also has a great Productivity Learning Pathway with some very useful resources.

Managing your boss

The second place to learn management is by managing your boss, also known as “managing up.” This is an extremely important skill in most if not all workplaces. Business with the Bulls*%t has some great, specific suggestions on how to do this. The key is to take your boss’s perspective of the work that needs to be done, and then act so as to make it happen. It means knowing the details of a particular task even better than your boss does, so that you can anticipate what kind of time and attention will be needed from your immediate supervisor and also his or her supervisors. It means seeing how your work fits into the bigger picture, identifying gaps, and filling them in.

Managing the work

One of the best ways to get management experience is to manage a process with a specific desired outcome. Even if no one reports to you on their day-to-day work, you can still get valuable management experience by taking the lead of an ad-hoc team that is expected to produce a certain product or result.

Management = harnessing motivation

I do believe that the best place to learn management is in the classroom - just not as a student. I spent two years as a middle school teacher, and looking back on that experience, I’ve come to understand it as an excellent crash course in management. In fact, teachers even use the term “classroom management” to describe techniques for keeping students on task. The more motivated and self-disciplined people are, the less they need to be managed by someone else. Children are not known for their self-discipline, which is why management in the classroom can be a trial by fire. But a good teacher can always tell you what the students are supposed to be doing - and tries to minimize the time that students are passively absorbing information. Likewise, teachers who make classroom management look effortless are those who are able to understand and harness the innate motivations of their students.

Shouldn’t a good manager be able to do the same for their employees? If you give people work that uses their talents, engages their interests, and then allow them to do the work in the way they see fit, they will require very little management from above. And a manager who understands the value of his or her employees’ time will likely ask them to spend less time in meetings where their only expected role is to absorb information.

The purpose of an MBA

I’d be curious to hear from readers - what do you think is the purpose of an MBA? Are there management skills that are no easier learned as a student in a brick-and-mortar classroom than as an online student? If so, what do you see as the best way to pick up these skills?

by Laurie Pickard | Sep 7, 2014 | MOOC MBA Design, Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

Most of the discussion about MOOCs and their advantages has focused on price (cheap or free) and teaching methodology (flipped classroom, lectures that can be viewed again and again). But as I am discovering, a MOOC-based learning program has two other much less-discussed advantages, especially for working professionals – customizability and immediacy.

As you know if you’ve been reading this blog, my goal is to mimic a traditional MBA education using MOOCs and other free resources. I’ve used the curricula of top MBA programs like Wharton, Harvard, and Stanford to come up with my list of courses and topics. (If this is something you’re interested in, you can find more info on my Curriculum page, or on the MBA Learning Pathway on SlideRule, which I helped to create). But recently I strayed from the traditional MBA curriculum to take a course on Social Psychology, and I’m very glad I did.

Somehow I managed not to take any psychology courses in college, despite having an interest in the subject and the fact that my roommates in both undergrad and graduate school were psych majors. It seemed like a hole in my education, and I thought a bit of education on the subject as might serve me while navigating interpersonal relationships in the world of work. Even though it isn’t a topic that is typically covered in business school, taking this course has convinced me that it should be. Social Psychology was packed with pearls of wisdom about perception, biases, and decision-making – all relevant to work in any office. One of the most interesting units was on group behavior, covering such phenomena as the Abilene Paradox, in which fears of non-conformity cause a group to arrive at a decision that no one actually thinks is a good idea. Being aware of this tendency and taking simple steps to counter it can actually prevent a group from going down an unproductive path.

Because I am setting my own curriculum, and because the entire universe of MOOCs is open to me, I am able to tailor my curriculum to very personal specifications and to include courses like psychology that aren’t covered in most MBA programs. I see this as being a great advantage of my chosen method of study.

My next set of courses also includes personally relevant offerings that aren’t always in the B-school lineup. One is Supply Chain and Logistics Fundamentals, the first in MITx’s long-awaited supply chain and logistics management series. The other is a course on evaluation of social programs from MITs Poverty Action Lab, which pioneered the use of randomized control trials for international development interventions. The latter, by the way, will be my first course on data analysis.

As I did with Social Psychology, I’m straying outside of a narrowly-defined business curriculum to take Evaluating Social Programs. While my overarching goal is to acquire a particular set of business skills, I am interested in any course with the potential to make me a better professional. As a designer of social programs and a consumer of program evaluations, my expectation is to be able to put what I learn in this course into practice in my current job. Which brings me to the second less-discussed advantage of a MOOC education – immediacy.

While I suppose any study-while-working program has this advantage, being able to use new knowledge and skills immediately in a real-world setting is enormously valuable for cementing what you’ve learned. MOOCs also offer another kind of immediacy – there is almost no cost to changing your mind. If you discover that a course is not what you were expecting, or doesn’t meet your needs, you can choose to study something different without waiting an entire semester and without losing any money. The only sunk cost is the time you’ve already put in to the course. In both of these ways, the feedback cycle on MOOCs is short. If, like me, you’re mapping out a series of MOOCs to achieve a larger educational goal, you can easily course correct if you need more or less of a certain topic, or if you discover gaps in your learning program.

I’m not sure how many “non-MBA” courses I’ll end up taking over the course of my studies, just as I’m not sure how many courses in finance I’ll include. It depends on the opportunities that arise and the learning needs I discover along the way.

by Laurie Pickard | Aug 22, 2014 | Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

I’ve posted a couple of articles recently on the No-Pay MBA Facebook page suggesting that perhaps the low completion rates in MOOCs are not evidence that they are a failed experiment. As an Atlantic article recently put it,

“Out of all the students who enroll in a MOOC, only about 5 percent complete the course and receive a certificate of accomplishment. This statistic is often cited as evidence that MOOCs are fatally flawed and offer little educational value to most students. Yet more than 80 percent of students who fill out a post-course survey say they met their primary objective. How do we reconcile these two facts?”

I’d like to add my voice to the chorus of people who are saying that maybe it’s completely understandable that only a slim minority of MOOC registrants make it all the way to the finish line.

The way I see it, there are two ways MOOCs can be valuable. A MOOC can either build your knowledge about a particular subject, or it can build your skills to apply knowledge in a particular way. I’ve written about my strong preference for skills building courses, but I see the value in both types of learning.

Ways of knowing

One of the things I’ve found most valuable about studying business via MOOC is the process of discovering – and putting firmer boundaries around – what I don’t know. It’s like the elephant parable, which you have probably heard if you have ever done any type of leadership or team-building retreat.

Basically, a bunch of people in a dark room are all standing around an elephant, touching it and describing what they feel (“It’s soft!” – the nose; “It’s rough and hairy!” – the skin; “It’s smooth and hard!” – the tusks) and trying to figure out what it is. Eventually they figure out that it is an elephant, but only with everyone’s input – hence the team-building connection. (Just as an aside, having been charged by an elephant, I can tell you that it’s probably not a great idea to put one in a dark room and let a bunch of people feel it up. )

Photo credit: Ethan Handel

Photo credit: Ethan Handel

For me, putting together an MBA curriculum is like the elephant parable. Each course provides information about what an MBA really is. The elephant begins to take shape. Even as I realize how many things I still don’t know about it, I start to recognize it for what it is. I refine my understanding of it.

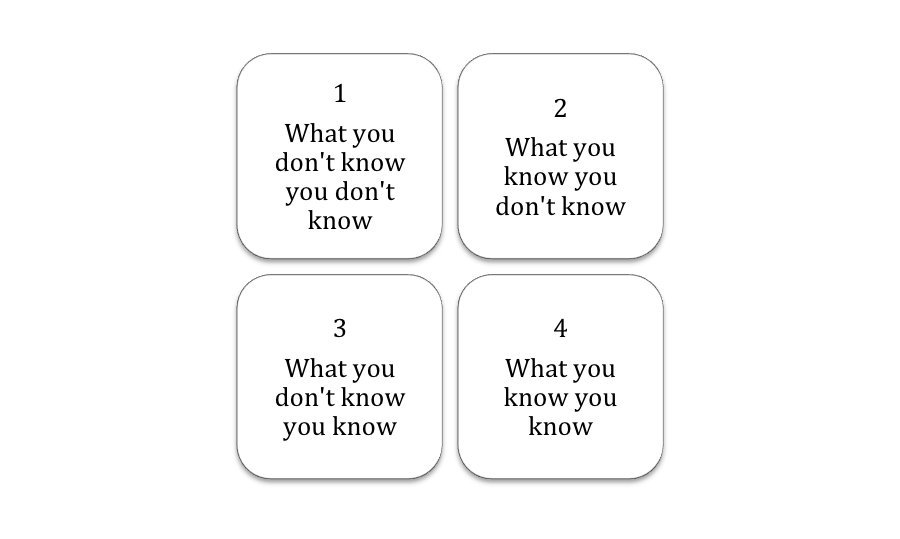

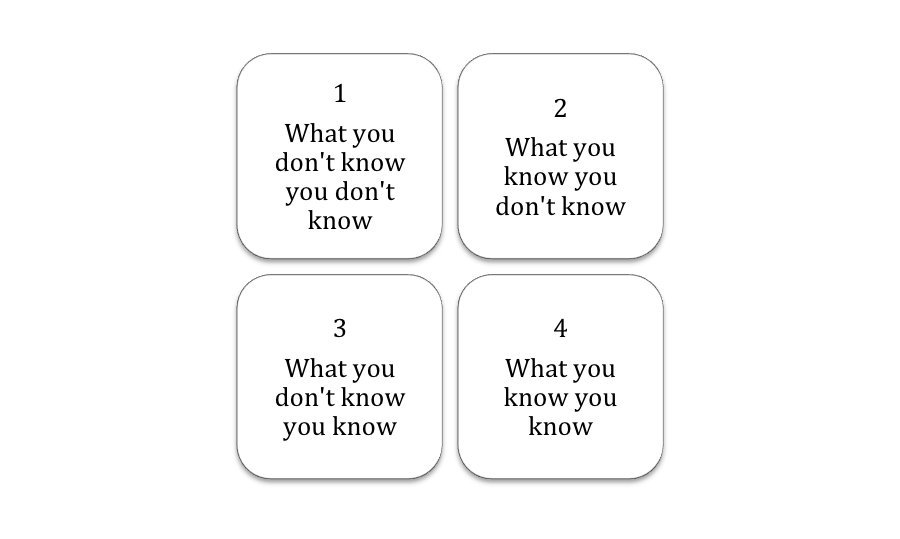

If you ever work with me you will learn that I think in matrices. It’s a good thing I was born into the information age because without Excel I basically wouldn’t have a way of organizing my thoughts.

Here’s one:

MOOCs are really good for moving from Box 1 to Box 2 – that’s knowledge building. For example, prior to taking a course on corporate finance, I would have been hard-pressed to even identify the types of situations in which corporate finance is used. Now, while I am not an expert in the subject – you wouldn’t hire me to value your company prior to a sale – I am conversant in financial terminology. That is valuable in and of itself, apart from any skills I may have learned.

MOOCs are really good for moving from Box 1 to Box 2 – that’s knowledge building. For example, prior to taking a course on corporate finance, I would have been hard-pressed to even identify the types of situations in which corporate finance is used. Now, while I am not an expert in the subject – you wouldn’t hire me to value your company prior to a sale – I am conversant in financial terminology. That is valuable in and of itself, apart from any skills I may have learned.

MOOCs can also move you from Box 2 to Box 4, though it is more difficult. Moving from Box 2 to Box 4 is what happened when, after learning that corporate finance is used to make investment decisions, I learned how to calculate the net present value of an investment.

MOOCs can even generate movement from Box 3 to Box 4. You might say Box 3 doesn’t exist – how can you not know something you know? Well, sometimes you realize that a concept you understand very well is called by a different name – like the fact that my employer, USAID, uses the term “cost-benefit analysis” for what I know as “net present value.” Sometimes you find that something you intuitively understand actually has a formal definition and is associated with particular methods. For example, my course on business strategy validated my matrix method, which I had no idea was part of business strategy until I took that course.

In fact, this type of movement – discovering what I didn’t know I knew – has been crucial in providing me with the confidence to present myself as someone who can offer most – if not all – of what an MBA-grad can offer. With all the hype surrounding MBAs, the de-mystification of the degree is really useful. By the way, if you are someone who hires MBAs or who competes with MBAs in the job market I highly recommend you at least audit some business MOOCs as a way of understanding what you’re dealing with.

It’s all about incentives

For those who are using MOOCs to build knowledge, watching a few videos may be enough. As the quote at the beginning of this post suggests, most students come away from the MOOC experience satisfied.

For those of us who are interested in building skills, completing the assignments may be more important. But even for us, what is the incentive to complete every course requirement and earn a Statement of Accomplishment?

I’ve set up this whole website basically as an incentive to myself to complete my courses. Because finishing courses is hard, and you need a good reason to do it. MOOC certificates don’t have any proven value – at least not yet, and certainly not in comparison to a degree. If finishing a course – meaning that you’ve earned a certificate – won’t provide any marginal value over watching some videos and possibly completing an assignment or two, then it’s really not surprising that most people don’t do it.

Question: Without this blog, would I be wiling to stick it out for every course?

Answer: Probably not.

Capturing value

Now for the big question:

How will anyone capture value from all the knowledge and skills that MOOCs are building?

MOOCs are most certainly creating value. All that learning is important. And someone will figure out how to monetize it – probably soon.

Maybe one day I’ll even be able to trade my set of certificates in for a degree, though I doubt it. A more likely scenario is that I will be able to convince an employer that my MOOC education has equipped me with skills and knowledge that have increased my productivity – and will pay me accordingly.

by Laurie Pickard | Jun 6, 2014 | Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

This post is the second in a series on the market for MOOC-based education.

Here’s the paradox of MOOC education: while MOOCs offer the greatest potential for those lacking access to university education, so far the majority of the people who use MOOCs (nearly 80% in one study, 66% in another) already possess university degrees. Some people have taken this statistic - along with the finding that over 90% of students don’t finish the MOOCs they register for - as evidence that MOOCs are a failed experiment in increasing access to higher education.

But question is not, are MOOCs a failure? Rather, the question is, how can MOOCs better serve the market?

In the first post in this series, I described two markets for higher education – one comprised of selective colleges and universities and the students who attend them, and another that can be characterized as non-selective. Understanding the differences between these two markets is key to finding sustainable business models within the MOOC space. As I said in my previous post, the key word to describe the needs of the market for non-selective higher education is ACCESS.

What would it take for MOOCs to reach their potential for expanding access to higher education?

In this post I will talk more about what it would take for MOOCs to meet the needs of the market segment that typically has lower access to higher education, focusing on three things - credentials, work-relevance, and support - and the business opportunities that exist in all these areas.

Credit for MOOCs

Given that MOOCs are in some ways competing with credit-bearing courses, it makes sense that people who don’t yet have degrees would be less likely to experiment with them. A degree holds proven value in the marketplace; non-credit courses, on the other hand, don’t. Therefore, it is understandable that people without university degrees would find little value in MOOCs as compared to for-credit courses at degree-granting institutions. This would explain, at least in part, why MOOC enrollees tend to be people who already have degrees.

But the equation is changing.

Legislators in Florida and California have been pushing universities to grant college credit for MOOCs. If MOOCs can lead to college credit, they may become more attractive to people who desire college credentials but don’t yet have them. Or consider the recent story about a woman who got her bachelor’s degree online, completely free of charge. The degree-granting institution is theUniversity of the People, an online university dedicated to expanding access to higher education. University of the People is the first online-only universities to get accreditation for a tuition-free degree. But other accredited schools like Western Governors University and Southern New Hampshire University already offer college credit based on competency – no classroom time required. These initiatives have the potential to greatly expand access to credentials for those who lack it, especially those students who would otherwise participate in the nonselective market for higher education.

Institutions that end up granting credit for MOOC course work will likely charge some type of fee - albeit less than the current cost of college credit. Universities might charge a fee to transfer credits in, course providers might offer special for-credit courses (paid, of course), and degree/credential-granting institutions might charge for admission, transcript review, or degree processing.

Work-relevant training could be more valuable than a college degree

In my previous post on this topic, I mentioned Harvard strategy professor Clay Christensen’s contention that in ignoring “vocational” education, traditional colleges and universities have left the door open for other education providers to fill this need. Employers complain that university graduates are not well-prepared for the world of work. It stands to reason, then, that some other type of certification for work-relevant training could supplant traditional college degrees as the preferred credential among employers, especially in certain fields. Online course providers like Udacity, Lynda, and Udemy have already adopted learning models that emphasize practical skills. And they are charging for these courses - though not nearly as much as most courses for college credit.

It isn’t hard to imagine that focused, job-specific online training could become more valuable than college degrees in technical fields like web development, or even that demonstrated mastery of commonly used programs and systems (Microsoft suite, Google programs) could be more attractive to an employer than a general degree.

So far only a handful of providers are working on this model, but it is easy to imagine other entrants coming into the market for work-relevant training. The existing providers focus on specific technical skills - computer programming, data analysis, and others. A provider that could train students and demonstrate their capability in areas like teamwork, writing, communications, critical thinking, or problem solving might also be able to charge for a credential.

High-touch support could increase completion rates

Even if the incentives were right for students to choose MOOCs over regular college courses - either because MOOCs could contribute credit toward a degree program, or could add up to a degree in and of themselves, or because some other credentialing system for work-relevant courses had emerged - low completion rates would probably still plague MOOCs.

If the challenges in non-selective brick-and-mortar colleges and universities are any indication, there is good reason to believe that drop-out rates would be high, and completion of an entire degree or other multi-course certification program within a timely fashion would be relatively rare. In fact, given the lack of social pressure and support inherent in online learning, these problems would likely be even more prevalent in MOOCs - even for-credit MOOCs - than in other kinds of classes.

The solution here is to find ways to make MOOCs higher touch. Just as in traditional colleges, extra support can go a long way to increasing completion rates. Some services to make MOOCs higher touch already exist – several MOOC providers and MOOC aggregators have introduced “learning pathways” or course series.

For example, the MOOC aggregator SlideRule is in the process of rolling out learning pathways in addition to the MOOC search and review feature it already provides. Learning pathways support students by taking some of the decision-making out of course selection. Or consider a site like Degreed, that offers learning pathways for both discrete skill sets (e.g. project management) and for degree equivalents in fields like business, computer science, and education. Degreed also helps students track their progress in all modes of online learning.

Another way to support students is through mentoring. Some sites,Thinkful and Udacity, for example, offer mentoring services to go along with their courses.

These support services are all relatively new, and there is still plenty of space for innovation.

The MOOC landscape is changing

With the right incentives and the right support, many more people could benefit from the boom in online education. While it is possible that many or most colleges will begin to feel pressure from emerging educational models, non-selective universities will likely experience the disruption first. It will happen as MOOC providers, online trainers, and third parties find ways to educate people more cheaply and efficiently, with fewer drop-outs, while providing credit, degrees or other recognized credentials. For the moment, there may still be a mismatch between what MOOC providers are offering and what the higher education market wants, but that won’t stay true for long.