by Laurie Pickard | Jan 1, 2015 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs, Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

Recently, I got the opportunity to speak with Anant Agarwal, CEO of edX. As the professor of edX’s first-ever MOOC and a proponent of access to education, Mr. Agarwal is one of the luminaries of online education. edX has over 3 million users from every country in the world. Of the Big 3 MOOC platforms, edX is the only one that is operated as a non-profit organization. Mr. Agarwal and I talked about a variety of topics, including how edX is making MOOCs more accessible to underserved populations, how online education can lead to employment, and of course, whether MOOC-based degrees are on the horizon.

LP: To start I want to say thank you. Thank you for speaking with me, but more importantly, thank you for putting all of this great content out into the world.

AA: You know, I’ve been seeing folks like yourself taking advantage of our resources to further their education, with the key words being “without incurring additional debt.” I think it’s great.

LP: Thank you. I have a bunch of questions so maybe I can just dive right in.

AA: Please do.

LP: First of all, I’ve been impressed with edX’s dedication to reaching populations that haven’t been served, but a lot of the press coverage of MOOCs that’s been negative has focused on the high educational level of people who are taking them. I’m interested in hearing whether you think the edX user population is a match with the target population you’re going for.

AA: Our mission was really to create a better world and provide access to education for learners all over the world. When we started out we had in mind learners frankly not such as yourself, student who in some sense need the education the most – college going students, high schoolers. Then when the data came back, we found that about 66% of our learners already had a college degree, about a third did not.

When the data came out saying a significant portion of the users already have a college degree, the view any for-profit MOOC providers took was, that’s where the market is, how do we serve that market? We’re a non-profit, and the view we’ve taken is the exact opposite. Which is, look, as part of a non-profit mission we’ve set out to solve a certain type of problem, and so rather than react to market forces, we have to change what we’re doing to really reach the kind of people we need to reach.

So, we launched a high school initiative, we started partnerships with many developing countries, we open-sourced our platform, all to try to reach that demographic. With the high school courses, for example, we’ve really moved the needle. For those courses only 50% of the learners already have a college degree. Also, it turns out that of those that have a college degree, parents and teachers are a substantial part. So we have ways in which we can reach our goals.

This is not to say that we don’t serve people who already have college degree, we do — we want to target learners from 8 years of age to 95 in a model we call continuous lifelong education — it’s just that we have to travel the extra mile to reach the people that really need it. In some sense this is probably not what you want to hear since you yourself are in that 66%.

LP: That’s true, but I still find that the courses on edX are extremely challenging, and when you provide challenging content, people who are seeking a challenge will appreciate it no matter where they come from or what their background is.

AA: Maybe you’re right there, Laurie. We attract a certain demographic, people who like a challenge. And that said, many of our courses require prerequisites. Let’s say you have a learner in Africa, and they want to take a great course in entrepreneurship or innovation or management, and there’s some pretty deep mathematics associated with it. You have to have the basic mathematics courses first before you can even conceive of taking those courses. That’s why we’re working to come up with the prerequisite courses all the way from high school to college so that we can create pathways for students no matter where they are in their education.

LP: Even though I may not be the typical developing world student, I am a learner taking MOOCs from Africa. I’m interested in hearing more about how MOOCs can be useful in a developing world context. I’m curious to hear how you see MOOCs making inroads into geographies without great access to higher education.

AA: Here, I can speak from the heart since I grew up in India. Some of my own experiences growing up shaped my own thinking and the thinking around what we are doing. Access to education for people in the developing world is a big part of what we want to do. In terms of that demographic, it turns out that the types of courses matter a lot. For example, the poverty course from Esther Duflo and Banerjee from MIT, it focuses on issues of poverty and development, that course gets a lot of students. So first of all is the type of courses, second of all the translations. There have been translations of the platform into many languages – Hindi, for example, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Mandarin Chinese, and so on. We’ve also created partnerships. For example, SocialEdu is a partnership with Facebook, the Government of Rwanda, Nokia, and Airtel, to provide mobile access to courses on smartphones. We’re doing these partnerships with Facebook and others to see if we can improve access in parts of the world where people need it the most.

LP: Another question that’s on my mind is about the link between MOOCs and future employment. I think it’s something that is very important to a lot of people who are taking these courses. What do you think about the connection between MOOCs and employment? Is there a pathway there?

AA: Absolutely. So at the end of the day if this is just a curiosity, well that’s fine, but we really want to help people. And finding jobs is one important area. In fact, we did a pilot about a year and a half ago where we tried to help about some of our students get jobs, and we could not place a single student. And the reason is that many HR departments didn’t understand the MOOC credential. Now things may have changed. There was a recent study done by RTI in which 70% of the employers surveyed indicated that they would look favorably on MOOCs mentioned in a resume of people that apply.

Now we’re working with organizations to help people find jobs. The most salient example is a partnership we did with a grassroots organization called LaunchCode, an experiment we called The St. Louis Experiment. They partnered with us with the thought that people can learn how to code, and a lot of companies need people who can do coding jobs, but without having a degree or a certificate HR departments weren’t looking at them. So we partnered with LaunchCode, and we got the CEOs of 100 St. Louis companies to sign up and agree to hire people with MOOC credentials. LaunchCode did a boot camp, and as part of that a large number of students took the edX CS50X Computer Science course from Harvard. Already this experiment has placed more than 100 people into jobs.

We have to make ground up change in the way people think, and we are doing it. The White House has gotten very interested in this, and they have encouraged us to work with LaunchCode to take this national. We’re starting with Miami next and will see where we go from there. So really, we’re doing a number of things that you would maybe not see from a for-profit startup. A lot of the efforts are simply things we believe we should do and there is no monetary benefit.

LP: You mentioned that when HR sees MOOCs on a resume, they still have a need to see a degree or some sort of certification. So I wonder, do you think that we will eventually see degrees made up entirely of MOOCs? Is that what’s coming next?

AA: Yes. I believe that will happen within the next 5 years. Actually, many of our university partners have expressed interest in doing something like this. There’s a lot of interest in making this happen, and I do believe it will happen.

by Laurie Pickard | Nov 23, 2014 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs, Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

Even though MOOCs don’t run on a semester schedule, I still like to think of my business education in those terms. As I near the end of the fall semester of my second year of self-made B-school, I’d like to reflect on some of the highlights of the past four months.

I talked to some very interesting people

I shared my thoughts on MOOC education with a grad student in Switzerland, answered some thought provoking questions from a startup in Bulgaria, and met a dynamic CEO who shared his insights on how employers see MOOC education.

I valued my coursework at over $50,000

I was recently asked how much my MBA coursework to date would have cost at a traditional university. Here’s my back of the napkin calculation: assuming $1000 per credit hour and 3 credit hours per course, I have racked up over $50,000 worth of free courses!

I facilitated a MOOC

Last year the State Department teamed up with Coursera to provide facilitated MOOC courses at embassies around the world as part of the MOOC Camp Initiative. In October and November of this year, I served as facilitator of one of these camps a the U.S. Embassy in Kigali, Rwanda. The course was “Beyond Silicon Valley: Entrepreneurship in Transitioning Economies” - perfect for the Rwandan context. I worked with an inspiring group of young Rwandan entrepreneurs, and even managed to arrange a Skype session with Professor Michael Goldberg.

A professor asked me to take his MOOC

One of the most exciting things that happened this semester was that a professor reached out to me and asked me to take his MOOC. And I’m glad he did! Professor George Siedel teaches an excellent course titled Successful Negotiation. Which brings me to my next highlight…

My best course assignment so far

The final assignment in Successful Negotiation is a negotiation exercise. The whole course builds up to this negotiation. Students in the course choose a negotiation partner, and each student is assigned one of two roles. The scenario was detailed enough that there was a lot to work with and plenty of opportunity to put the concepts in the course into practice. In addition to being a great practical assignment, it was a perfect solution to the problem of lack of student interaction in a MOOC. My only complaint about this course was that there was only one such negotiation. If more are included in a subsequent offering, I may end up taking this course again.

My most difficult course so far

Perhaps I shouldn’t speak too soon since I haven’t finished this course yet, but I am six weeks into Supply Chain and Logistics Management from MITx, and I am on track to pass. MIT courses are HARD. In many courses, a straight A is no big achievement, but in an MIT course, a 60% is a passing grade, and it’s difficult to get. This course has required me to reach back into the recesses of my memory to high school algebra and calculus, to dust off my college statistics, and to master Excel functions I didn’t even know existed. I sometimes feel like I did as a child taking piano lessons, when I would get so frustrated about a piece that I would end up practicing through tears until I finally got it. This course doesn’t make me cry, but it does sometimes test the limits of my determination. When I get that certificate of completion, I will feel very proud.

Next: winter term

I went to a college that had a winter term, during which students had time to do an intensive project or internship in between the fall and spring semesters. I’m taking a winter term this year to do a few practical business projects involving team work. First, I’m in a NovoEd course (co-presented with +Acumen) that involves financial modeling of a social enterprise and a substantial group work component. Second, I’m planning to do some group business games and simulations - more on that later. Finally, as treasurer of the employee association at the US Embassy in Kigali, I’m working on a restructuring of the Embassy’s commissary business. With these three group activities I’m planning to recreate at least part of the social learning component of a traditional degree.

by Laurie Pickard | Sep 20, 2014 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs, Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

What is the purpose of an MBA? I’m sorry to get all philosophical on you, but someone asked me the other day, and while I was able to rattle off a list of skills that I have learned since embarking on this journey (reading a balance sheet, calculating NPV, analyzing recurrent processes and finding inefficiencies,etc.), I wasn’t able to come up with an overarching statement of purpose regarding what an MBA is supposed to be or do.

The conversation left me thinking about whether an MBA is supposed to be management training, or whether it is more technical training. In trying to answer this question, I went back to an excellent article by Brooke Allen called ‘How to talk yourself out of getting an MBA.’ The article refers to a book called Managers, Not MBAs, which is also a great read. Both of these works set up the MBA as a management degree, then proceed to tear it down. As Henry Mintzberg, the author of Managers, Not MBAs says,

“It is time to recognize MBAs for what they are - or else close them down. They are specialized training in the functions of business, not general educating in the practice of managing. Using the classroom to help develop people already practicing management is a fine idea, but pretending to create managers out of people who have never managed is a sham.”

I suppose I agree with Mintzberg, and with Allen, that you can’t expect to learn how to be a manager from an MBA program. From what I’ve seen so far, getting an MBA is unlikely to make someone a good manager. But maybe that’s not a problem. I’m finding plenty of value in learning the “functions of business” and in learning to perform the types of analysis that are particular to business. In fact, maybe a better title for the degree than Master of Business Administration would be Master of Business Analysis.

But what if what you really want to learn is how to be a manager? If you can’t learn management in a business administration program - and frankly I agree with the two previously mentioned authors that if this is what you want to learn, then business school is probably not the place for you - where do you learn that skill set? I have four suggestions on where to start.

Managing yourself

I recently read a book called Business Without the Bulls%*t, in which the author starts the book by claiming that everyone is essentially a freelancer. What he means by this is that a good worker needs to manage him or herself - understand what is expected of you at work, and get things done well and on time without much oversight. The first place to learn management, then, is by managing oneself. You can find lots of great personal productivity tips on YouTube. Degreed.com also has a great Productivity Learning Pathway with some very useful resources.

Managing your boss

The second place to learn management is by managing your boss, also known as “managing up.” This is an extremely important skill in most if not all workplaces. Business with the Bulls*%t has some great, specific suggestions on how to do this. The key is to take your boss’s perspective of the work that needs to be done, and then act so as to make it happen. It means knowing the details of a particular task even better than your boss does, so that you can anticipate what kind of time and attention will be needed from your immediate supervisor and also his or her supervisors. It means seeing how your work fits into the bigger picture, identifying gaps, and filling them in.

Managing the work

One of the best ways to get management experience is to manage a process with a specific desired outcome. Even if no one reports to you on their day-to-day work, you can still get valuable management experience by taking the lead of an ad-hoc team that is expected to produce a certain product or result.

Management = harnessing motivation

I do believe that the best place to learn management is in the classroom - just not as a student. I spent two years as a middle school teacher, and looking back on that experience, I’ve come to understand it as an excellent crash course in management. In fact, teachers even use the term “classroom management” to describe techniques for keeping students on task. The more motivated and self-disciplined people are, the less they need to be managed by someone else. Children are not known for their self-discipline, which is why management in the classroom can be a trial by fire. But a good teacher can always tell you what the students are supposed to be doing - and tries to minimize the time that students are passively absorbing information. Likewise, teachers who make classroom management look effortless are those who are able to understand and harness the innate motivations of their students.

Shouldn’t a good manager be able to do the same for their employees? If you give people work that uses their talents, engages their interests, and then allow them to do the work in the way they see fit, they will require very little management from above. And a manager who understands the value of his or her employees’ time will likely ask them to spend less time in meetings where their only expected role is to absorb information.

The purpose of an MBA

I’d be curious to hear from readers - what do you think is the purpose of an MBA? Are there management skills that are no easier learned as a student in a brick-and-mortar classroom than as an online student? If so, what do you see as the best way to pick up these skills?

by Laurie Pickard | Aug 15, 2014 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs

I’ve always had a distaste for the idea of marketing. I saw marketing as a fluffier part of business – as compared to subjects like accounting and finance – and I was uncomfortable with the idea that corporations actively work to shape our desires. I might not have taken a marketing course at all, if it weren’t for the fact that I’m using MOOCs to mimic a degree-bearing MBA program course-for-course, and most if not all MBA programs include at least one course on marketing.

Introduction to Marketing, a MOOC from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, quickly disabused me of my mistaken notions about marketing. In fact, by the end of the course I was convinced that marketing is a central component of business strategy – perhaps the central component. The course is taught by three professors – Barbara Kahn, Peter Fader, and David Bell. Each prof teaches one unit – Branding, Customer Centricity, and Go-to-Market Strategies, respectively. Introduction to Marketing is part of the Wharton foundational series – along with Introduction to Accounting, Introduction to Operations Management, and Introduction to Corporate Finance. I’m still counting my lucky stars that one of the top business schools in the country started giving away free online versions of its core courses just as I started putting together my free version of an MBA.

Without further ado, let’s go through my three-part rubric for evaluating online courses.

Am I checking my email during the video lectures?

No issues in this department. The lectures were interesting and engaging. Each professor’s deep and obvious passion for his/her subject matter helped to keep my interest level high. Having three distinct perspectives also contributed to my experience. I appreciated that the videos were clean – often, the professor would speak against a white background, with nothing else on the screen. Rather than relying heavily on slides, key words would appear on the screen in the white space surrounding the professor. The lack of visual distraction helped me stay focused on the content.

As previously mentioned, this course changed my view of marketing. Marketing is not just about advertising – it’s about MARKETS. Who are your customers? Where do you find them? What value do you propose to create for them, and how do you let them know about it? How do you address the fact that your customers are individuals, with unique desires and preferences? Professors Kahn, Fader, and Bell covered these and other topics in a conversational but highly informative manner.

Do the assignments require serious thinking?

Unfortunately, the assignments in this course offered little of substance. There were weekly readings and a quiz after each of the three units. The quizzes were good, as were the readings, but I would have appreciated at least one assignment requiring me to apply some of the concepts I had learned.

Is there a practical application for what I’ve learned?

The information covered in this course is extremely practical, as it informs businesses’ orientation towards their customers. The professors did a good job of using real businesses to illustrate their points. Again, the one thing I felt this course was missing was a “how-to” element. While I could clearly see that marketing concepts have practical applications, I would have liked more instruction – and more practice – on how to apply these concepts myself.

The bottom line

Overall, I have found the Wharton courses to be very high quality. Introduction to Marketing is no exception. This course is well worth the 1-2 hours per week it takes to watch the videos and read the assigned readings. However, you will have to look elsewhere to find ways to practice applying marketing concepts.

This post originally appeared on the website Poets and Quants.

by Laurie Pickard | Aug 2, 2014 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs, MOOC MBA Design

I just finished another outstanding course, “Foundations of Business Strategy,” taught by Michael J. Lenox of the Darden School of Business at the University of Virginia. Like Wharton, Darden is a leader in providing B-school content via MOOC. This course was dense with content. In just six weeks we covered:

- The concept of strategic analysis and the impact of competitive markets on business success

- How to analyze industry forces

- How to analyze firm capabilities

- How to analyze competitive dynamics

- How an organization can best position itself competitively to create value

- How to analyze firm scope

As you can tell from the number of times the words “how to” appear in the above list, this course was very focused on building practical skills. In addition to two or so hours of video lectures each week and readings from a book called The Strategist’s Toolkit, each week also included a case study from a particular industry – also with reading and analysis required. Additionally, a key requirement of the course was to conduct a strategic analysis of a real business and draft a report with hard data and specific strategic recommendations.

Six weeks. Normally, I like MOOCs that hold me to a schedule; the schedule keeps me focused and prevents the course from dragging on. However, while the content in this course was fantastic, my one complaint was that I didn’t really have time to engage with all of it. I normally spend about 4 hours per week on a course. This one could have easily used 10. In fact, I may take this course again next time it’s offered. That’s the beauty of MOOCs.

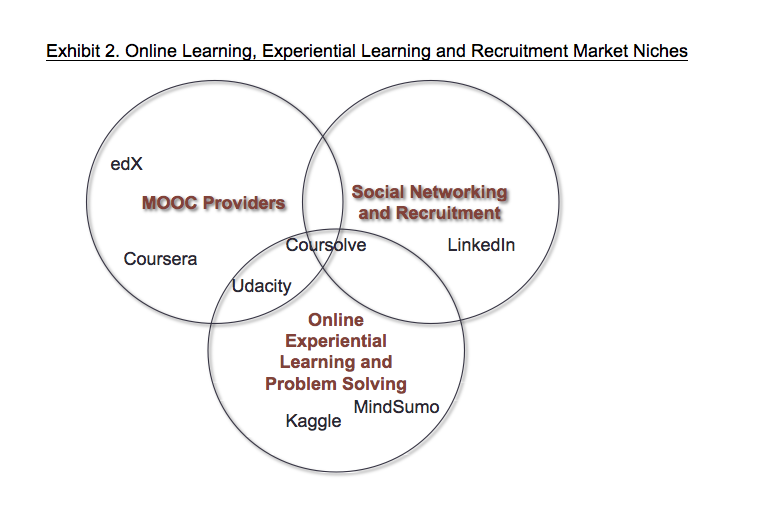

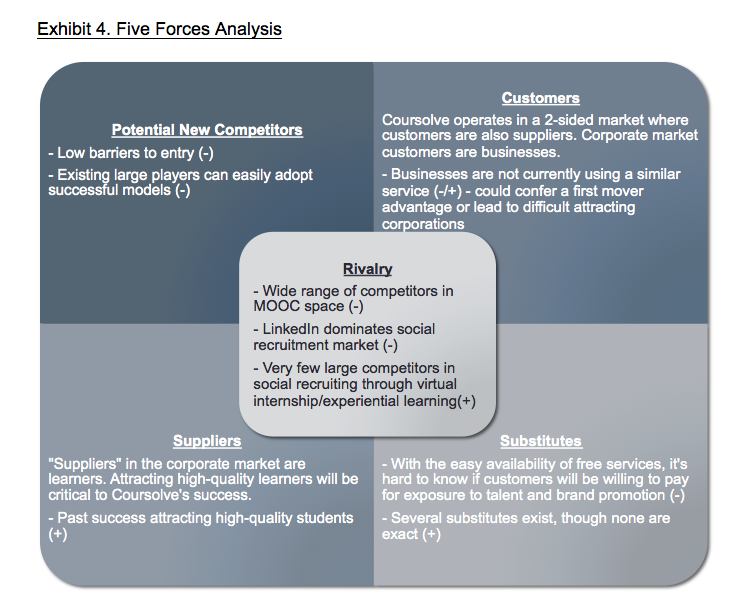

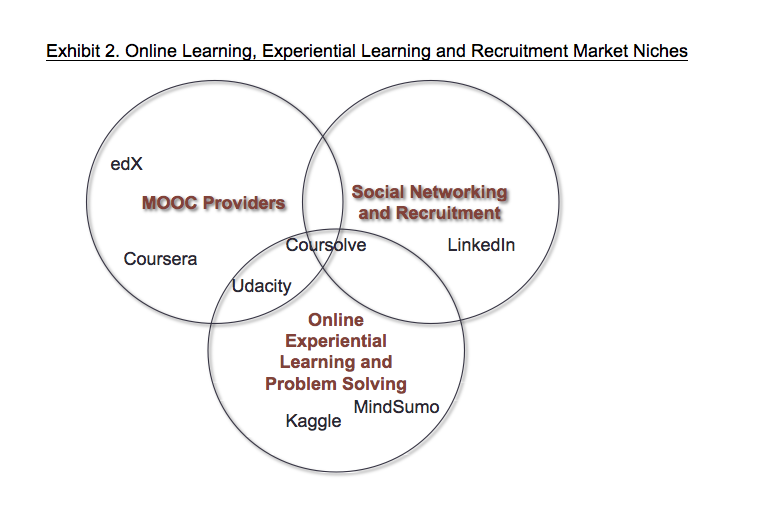

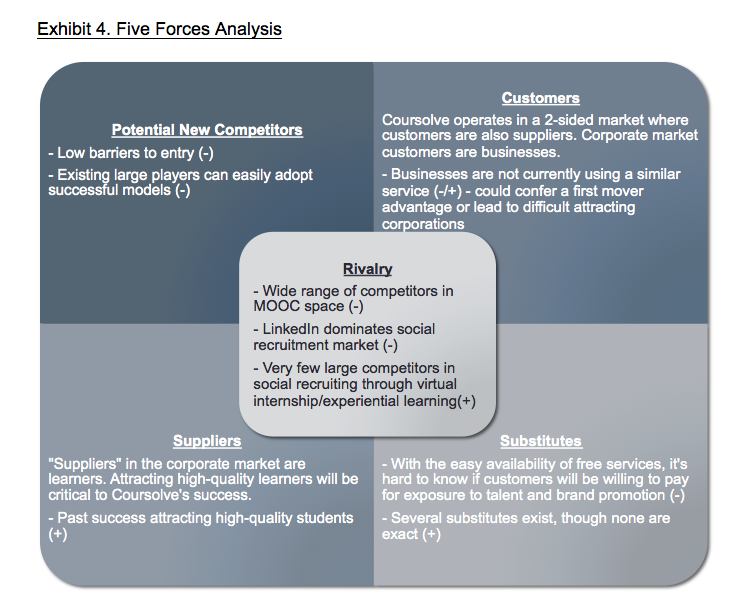

What I chose to focus on this time around was the final project. I registered for this course in part because I had recently heard about Coursolve, an online experiential learning platform that connects MOOC students with real companies. The companies post needs that correspond to the skills covered in the MOOCs, and students can try out their new skills solving real-world problems. Rather than basing my final project on a well-known company with which I had no personal connection, I was able to browse the needs posted on Coursolve and choose a real-world situation to work on.

If you’re taking business MOOCs and you haven’t heard of Coursolve before, I strongly encourage you to check out what they’re offering. The needs relevant to my business strategy course ranged from an HR company trying to figure out the needs of its customers, to a mining company looking to go public, to an Indian clean tech company trying to come up with a marketing plan. For my final project, I chose to work with Coursolve itself, as this online startup is still crafting its own business model.

Between the case studies and the final project, which will be assessed by my classmates, “Foundations of Business Strategy” offered above-average opportunities for interaction, skill-building, and experiential learning. Some people question the ability of online courses to teach a subject like strategy. This course proved to me that it can indeed be done, and quite well.

by Laurie Pickard | Jul 20, 2014 | Community and Networking, Courses, Platforms, and Profs

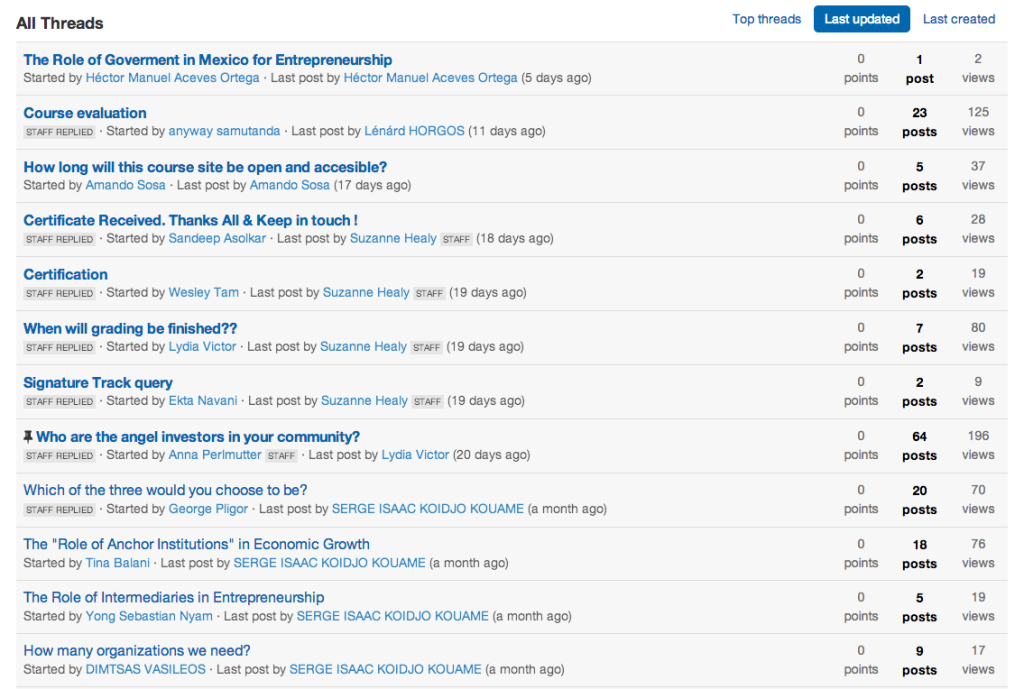

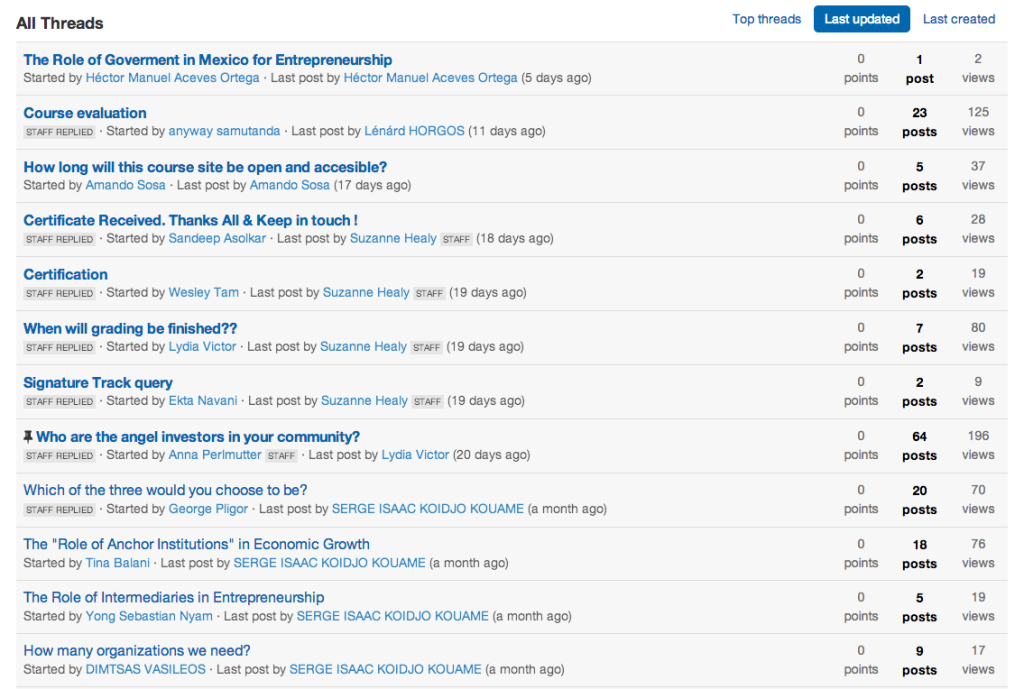

If you’ve been reading my blog for a while, then you know that my MOOC pet peeve is when professors require students to post on discussion forums as a part of the course grade. It creates a lot of meaningless chatter - one person writes something mildly intelligent, and a hundred others post something to the effect of “I agree.” In general, I avoid courses that come with such a requirement. But I decided to look past this bias when I registered for “Beyond Silicon Valley: Growing Entrepreneurship in Transitioning Economies.” As I’ve written previously, this course was enormously relevant to my work. So rather than let my negative feelings about obligatory posting get in the way of my experience, I decided to make the course a laboratory for experimenting with how to get the maximum value out of discussion forums.

Here is what I learned:

1. Skip the Introductions Thread

Maybe you want to glance through the introductions, skimming for anything particularly interesting. But in general, the introductions thread is a blur of names and nationalities and people expressing their excitement about the course. Instead of making that your starting point, I suggest thinking about the kinds of people you’d be most interested in engaging with or what you’re hoping to learn in the course. Then instead of reading post by post, search the entire discussion forum on those topics and see what comes up. For example, I usually start by searching on “Rwanda” and “Africa” to see who else is taking the course from my neck of the woods.

If nothing comes up, or if the posts on your topics of interest are scattered within the forum, start your own discussion thread based on geography, background, or field of interest.

2. Fill Out Your Profile, and Include a Photo

This is really important. Savvy social media users always do a bit of investigation on who they’re dealing with before responding to a post. This isn’t creepy, it’s smart. On your own profile, include a very short summary with one or two interesting facts about who you are and what you do, who you’re hoping to interact with in the course (optional), as well as links to any other social media you want people to reach out to you on.

If you’re stuck for what to write, try this template:

“I’m a _______________________ working on _________________________. I’m taking MOOCs in order to ______________________________. I’d love to connect with others who share my interest in _____________________ and _________________________. You can also find me on LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, and _________________________. “

For example:

“I’m an international development professional working on entrepreneurship and public-private partnerships in Kigali, Rwanda. I’m taking business courses as part of project to construct a free MBA equivalent out of MOOCs. I’d love to connect with others who share my interests in development and entrepreneurship or my enthusiasm for MOOCs. You can also find me on LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, or on my website at www.nopaymba.com.”

When others in the course post interesting comments, check their profiles before responding. You may find that you’re interacting with someone in the industry you’d like to move into, and you now have a great point of entry for a conversation.

3. Facilitators Make a Difference

The professor of “Beyond Silicon Valley,” Michael Goldberg, was a stellar forum facilitator. Throughout the course, I often wondered how he found the time to make so many personal connections, partcipate in so many discussions, and respond to so many comments. He helped keep discussions on track, made introductions among students, and generally kept the level of engagement high.

But not every course is led by a facilitator with as much verve and enthusiasm as Professor Goldberg. What then?

If you’re in a course that lacks strong facilitation, I suggest trying to play that role yourself. While they don’t have the star power of professors – who doesn’t like getting a few good strokes from the teacher? - students can also be facilitators. By taking a meta view of the discussion, trying to spark conversation, and focusing on connecting people, you the student can have a better forum experience and up your chances of making connections.

4. One Real Connection is Worth a Thousand Up-Votes

By far the most active group on the forum, and the group that seemed to get the most out of the course, was a group from Greece. They met in person periodically, developed real connections to one another, and used the forum as a supplement to a face-to-face conversation they were having. But what if, like me, you’re in a place where you can’t do that? Or what if you simply don’t have the time for in-person meet-ups?

It is tempting to gravitate towards the discussion threads where the most is happening – most posts, most up-votes, most people. But I suggest doing the opposite: find a niche where you can substantively engage with a few people on a topic you are passionate about; then focus on making one or two connections that are strong enough to take outside of the classroom.

I started “Beyond Silicon Valley” thinking I would form a group of people who could interact via video chat throughout the course – a sort of virtual study group. To that end, each week I created a discussion thread called “Africa Study Group.” A few times I floated the idea of a video chat, but no one expressed interest. I also joined the Facebook and LinkedIn groups for the course. Not much seemed to be happening there either.

By the end of the course, I hadn’t managed to get a stable study group going, but I did have some great conversations with an entrepreneur in Africa who shares my interest in the potential of MOOCs for the continent. I realized that in the end, this one connection was probably just as valuable as a study group would have been.

Overall, I’m still not sold on discussion forums, but at least now I can find some good in them. I’m curious as to others’ experiences in MOOC discussion forums. What’s your opinion on mandatory forum posting? What value have you found in forums?