by Laurie Pickard | May 10, 2014 | Career Development, Courses, Platforms, and Profs, MOOC MBA Design

This post has been updated for 2015! See the new post here:

https://www.nopaymba.com/pay-verified-statement-accomplishment-mooc-update/

I’m currently taking three courses – two from Coursera and one from edX. All three come with a final course certificate, and all three offer an upgrade option for that certificate. In my two Coursera courses, the “Signature Track” option comes with a “Verified Statement of Accomplishment;” in my edX course, I can choose to enroll as an “ID-verified” student to get a “Verified Certificate of Achievement.”

So far, I haven’t spent any money on course certificates. Frankly, I wasn’t convinced the first time Coursera asked me to join a course’s Signature Track, and I still don’t see the added value.

What exactly is a verified course certificate?

Both Coursera and edX offer essentially the same product. For a fee ($49 on Coursera, $25 on edX), you can verify your identity by submitting a typing sample and snapping your image on a webcam. On subsequent logins, the system makes sure that you are the same student as before. At the end of the course you get a slightly snazzier-looking certificate than you otherwise would, with the word “verified” on it.

The value proposition for this product is based on four assumptions:

1. Course certificates have value to students.

2. Students will cheat to get these certificates, so there is value in ensuring that the person who holds the certificate is the same person who completed the course work.

3. Webcam photos and typing samples are an effective way of verifying a person’s identity.

4. Employers (or other third parties) know the difference between verified and non-verified course certificates.

Why I haven’t bought any course certificates

First, I’m skeptical that course certificates themselves are valuable. I can hardly imagine that I’ll present my course certificates to future employers for the same reason that I don’t list my individual courses from undergrad on my resume. The totality of the program of study is much more important than any individual class. That said, some type of proof of course completion is probably worth something, especially if you can aggregate individual certificates into something bigger.

If certification is valuable, then it does follow that some students will cheat to get them. However, I’m not at all convinced that verifying that the same student logs in again and again is a good way to prevent cheating. For example, a student who wants to cheat could get answers from a person sitting next to him or her, while still meeting the typing and webcam tests. It would even be possible for one person to do all the work for a course under someone else’s name.

But let’s leave that to one side. Let’s assume that the verification process is a good way of providing proof that person X really did the work for a given course. Even then, and even if employers care about course certificates at all, I highly doubt that they know the difference between verified and non-verified certificates.

Let’s say that employers do care. What the verified option currently tells you is that the person in question was able to complete a course without cheating. That might mean a lot if you knew that the course was really tough, or if mastering the material was essential for some particular purpose. But for any old course, if I was able to sit through a few videos, answer a couple of quiz questions, and post ungraded comments on a discussion forum, do you as an employer really care that I was able to do that without having to cheat? I’m not buying it.

A course certificate I would pay for

If MOOC providers want to make money from course certificates they could do a few things.

1. Don’t give away any course certificates for free. The marginal difference between having a certificate and having no certificate is greater than the marginal difference between a regular certificate and an identity-verified certificate. There are probably more people willing to pay for any kind of certificate at all when certificates aren’t free than there are people who will pay for a premium certificate when regular certificates are free.

2. Include course difficulty or relevance ratings on the course certificate. Anyone who has taken a few MOOCs knows that the level of difficulty varies enormously from course to course. Likewise, coursework varies from immensely practical to merely interesting. Students know the difference. It would be easy enough to crowd source difficulty and relevance ratings to give a better indication of how valuable a given course certificate is.

3. Focus on strings of courses that demonstrate professional competency. Completion of a series of courses has a much greater potential to signal mastery than a single course completion certificate. edX has started to group courses in its xSeries. Coursera has begun to do the same with its Specializations. The models here are slightly different. edX charges for the courses themselves at about $100 per course, while Coursera charges only for the verified Statements of Accomplishment. I am excited to take a set of business courses from one of these providers, but so far none have been released. (I’m still waiting on MIT’s Supply Chain Management series through edX.)

4. Market aggressively to teach employers the value of course certificates. A certificate I would be happy to pay for would be one that employers find interesting or impressive. Even more valuable would be a certificate that signals to an employer, “If this person was able to finish this series of courses, then she must be capable of doing work in ______________________________ (insert field).”

I’d like to hear what others think about this. Do you pay for course certificates? If so, why? If not, why not?

by Laurie Pickard | Apr 12, 2014 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs

I’ve taken about a dozen business MOOCs so far as part of my effort to construct the equivalent of an MBA, for free. I’m always on the lookout for new courses, and I was excited when Coursera released “Financial Markets” with Nobel Prize-winning economist and Yale University professor Robert Shiller. I had previously come across another version of this course through Open Yale, a site run by Yale University where anyone can access no-frills video and audio of lectures that were delivered live in the classroom. I started the Open Yale lecture series but didn’t finish it because Coursera announced their version of the same course when I was only partway through. I generally prefer Coursera’s condensed, made-for-online format, so I stopped listening to the Open Yale lectures and signed up the Coursera version.

When I first got interested in MOOCs, I read several articles decrying MOOCs as furthering the phenomenon of “rock-star professors,” the idea being that big-name profs reduce the number of jobs available to lesser-known professors and diminish the quality of university teaching, since they typically teach to packed lecture halls where one-on-one interaction is practically impossible. Being an online student with no hope of actually speaking with my professors, I am excited about the idea that I might take a course from a renowned professor, even as one of thousands. Robert Shiller is about as renowned as they come. He basically predicted the 2008 financial crisis in his best-selling book Irrational Exuberance, and he won the Nobel Prize in Economics 2013, among many other career achievements.

Unfortunately, in its attempt to package Professor Shiller’s course for an online audience, Coursera missed an opportunity to use the MOOC format to surmount some of the obstacles inherent in teaching en masse. Instead, they managed to recreate many of the frustrations of a crowded lecture hall. Let me explain what I mean as we go through my three-part rubric for online courses.

Am I checking email during the video lectures?

This course passes the email test without a problem. Professor Shiller is clearly brilliant, the topics covered in the course are interesting and relevant, and the lectures are filled with history and anecdotes. However, the majority of the videos are the same lo-fi lectures I was watching on Open Yale, taken from when Professor Shiller taught this course in 2011. The sound quality isn’t great, the lighting is terrible, and the camera often pans away from the blackboard just as Professor Shiller finishes writing a formula. I often feel like a puny freshman in the back of the classroom, straining to see and hear what’s going on up front.

The best videos are the introductions to each week’s series of lectures, which Coursera produced specifically for this course. These videos are cheesy – each one features a different building on Yale’s illustrious campus – but the sound and lighting are good, and you don’t feel like an eavesdropper to a lecture that was made for someone else. These are also the videos in which Professor Shiller reflects on why, even with the bad image finance has acquired following the crisis, he still considers financial markets crucial to modern society.

Do the assignments require serious thinking?

The assignments for this course are composed of weekly quizzes and a peer-graded writing assignment. I was pleasantly surprised by the writing assignment, which required students to summarize an article about the psychological underpinnings of the financial crisis. The assignment was fairly rigorous, and peer grading worked better than I expected. It would have been even better if the peer graders had been able to provide written comments instead of just numerical scores, but that’s a minor complaint. The quizzes, however, are frustrating. They are certainly difficult enough, but they often test material that wasn’t adequately covered in class – for example, formulas that appear on the board for approximately 3 seconds before the camera follows Professor Shiller across the classroom and are never practiced. This is where Coursera was being lazy. Even if Professor Shiller himself was too busy to record new videos in which we could practice using these equations, surely one of the course’s three teaching assistants could have held a weekly section.

Is there a practical application for what I’ve learned?

I’ve mentioned before that I’m partial to courses that are short on theory and long on concrete skills. This course doesn’t exactly fall into that camp, but even though there isn’t a direct practical application for the material covered in “Financial Markets,” having an understanding of such markets is a necessary precondition for being an effective participant in them. This course will teach you what financial markets are, how they arose, and how they work today. Whether you are interested in using these markets, or just wants to have a better understanding of how they fit into our society, there is plenty of value to learning this material.

A missed opportunity

I think Coursera saw this course as a cash cow, an inexpensive way to turn pre-recorded lectures into a blockbuster MOOC featuring a star professor. They certainly built a lot of hype for the course; advertisements for it seemed to follow me around the web. But Coursera missed a chance to do more with the raw materials at its disposal. Any MOOC is a team effort. With Professor Shiller occupying the starring role, the rest of the team could have been called upon to flesh out the key concepts, just like in a live course where the big name professor is the draw and the TAs do the heavy lifting.

The bottom line

This course if definitely worth taking. Just don’t stress out about the math problems you can’t answer. Take this course to learn about the history and evolution of financial markets, to get a sense of the scope and purpose of these markets, to learn some terminology, and most importantly, to understand why an intellectual luminary like Robert Shiller thinks these markets are important to our society.

This post originally appeared on the website Poets and Quants.

by Laurie Pickard | Feb 15, 2014 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs

As I’ve mentioned previously, my goal in taking MBA courses is not to go into finance or consulting. Rather, I want to build skills that are relevant to the international development work I am already doing, and eventually to move from public sector development work to related work in the private sector. I am currently taking a course that is a great bridge between these two, aptly titled Subsistence Marketplaces.

Subsistence Marketplaces Professor Madhu Viswanathan

What I like about Subsistence Marketplaces is the difference in approach from previous courses I have taken on development, both in undergraduate and graduate school. This course looks at the markets that exist in places where much of people’s daily activity is about survival. It doesn’t ask why people are poor or analyze the interventions foreign governments have undertaken to help them; it doesn’t look at the history of poverty and development. Not that these more traditional approaches to studying poverty and development aren’t important, but it is refreshing to look at a subject I know well from a different angle.

In Subsistence Marketplaces we are trying to get inside the minds of poor consumers, understand their lived experience, observe how they operate in the marketplace and from there, design products to serve their market. I’ve seen this type of analysis before – in How to Build a Startup, where I learned the importance of mapping out “A Day in the Life” of your intended customer. This exercise helps to identify the daily frustrations the consumer experiences and the types of innovation that could result in a marketable product. For consumers living in poverty, it helps to understand the reasons – and there is always a reason - for behaviors that may not at first make sense to an outsider. For example, why buy from a store that charges higher prices? (Answer: it’s run by a neighbor who gives credit.)

Our ultimate goal in this course is to come up with a product that could be marketed to the mass of poor people who constitute the base of the economic pyramid, otherwise known as the BOP. In recent years some interesting solutions for BOP consumers have gotten a lot of attention, for example M-Pesa (mobile phone-based banking for the poor) and microfinance (credit and savings for the poor).

Our ultimate goal in this course is to come up with a product that could be marketed to the mass of poor people who constitute the base of the economic pyramid, otherwise known as the BOP. In recent years some interesting solutions for BOP consumers have gotten a lot of attention, for example M-Pesa (mobile phone-based banking for the poor) and microfinance (credit and savings for the poor).

Coming up with a product for the BOP is easier said than done. As any Peace Corps volunteer can tell you, poor people are experts at navigating their environments, and just because a new way of doing things sounds like a good idea to you – organic gardening, say – doesn’t mean people will rush to adopt it once you’ve told them the good news. You may have overlooked the voracious leaf-cutter ants that flout any attempt short of noxious pesticides at controlling their apetites, or any number of other impediments to adopting a new technology. The same goes for any product or intervention aimed that the BOP market; business people and development professionals alike can benefit from a rigorous analysis of their product/intervention’s value proposition within the context of the lives of the people they are trying to serve.

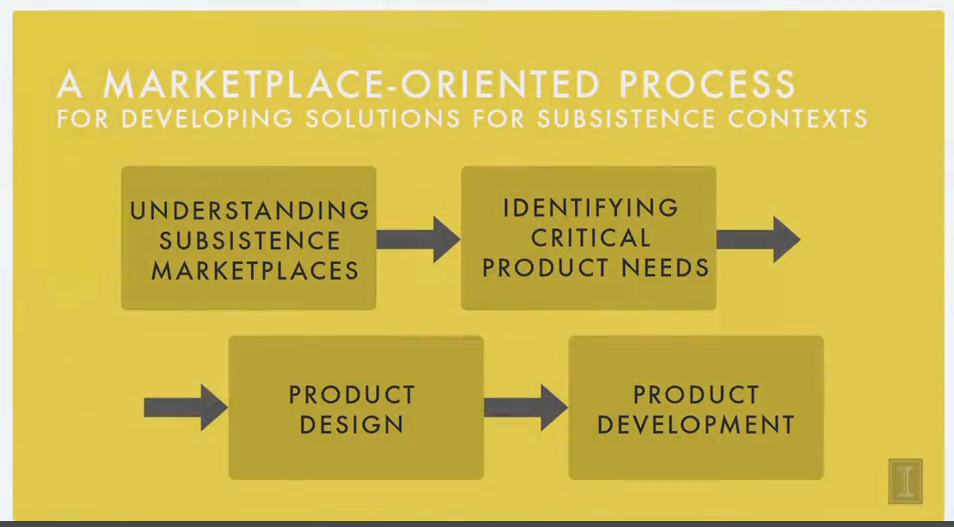

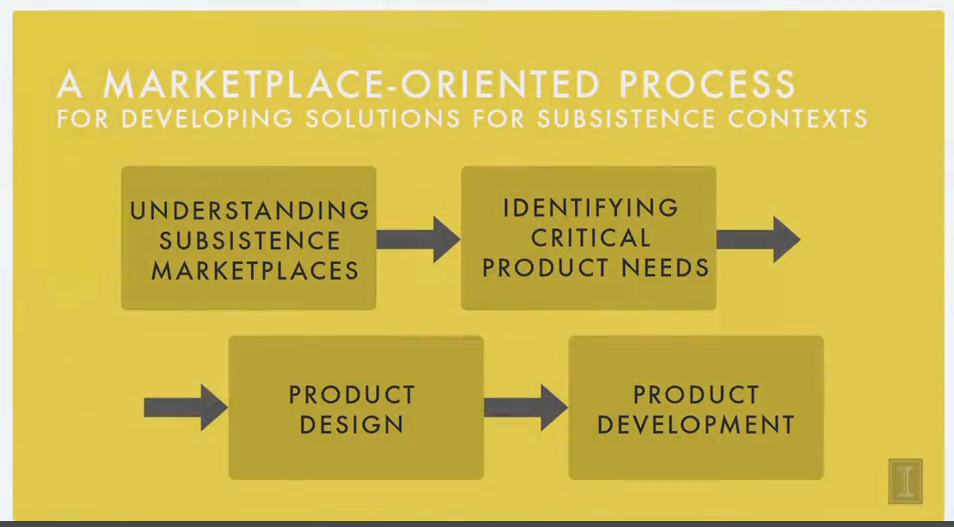

In product development, once you have developed an understanding of the lives of your customers, you move on to identify some of their most salient needs. From there, you pick a need that you think you can address with an innovative solution. Sounds simple enough, but it’s tough to come up with an innovation so useful that poor people will be willing to part with scarce money. I’m not sure if I’ll hit on anything brilliant by the time it’s due - so far, I haven’t managed to come up with anything that doesn’t already exist in the BOP market – but the assignment has got me scouting marketable solutions.

by Laurie Pickard | Feb 8, 2014 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs

I’ve started reviewing my courses on the website Poets and Quants. You can see the first one at: http://poetsandquants.com/2014/02/06/the-best-mooc-for-entrepreneurs/. I’ll be doing these reviews about once a month, so stay tuned for more!

by Laurie Pickard | Jan 13, 2014 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs

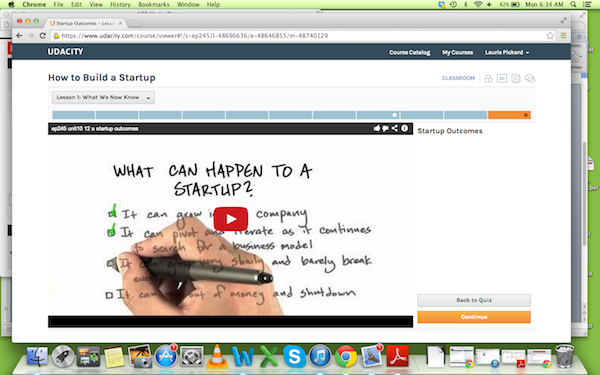

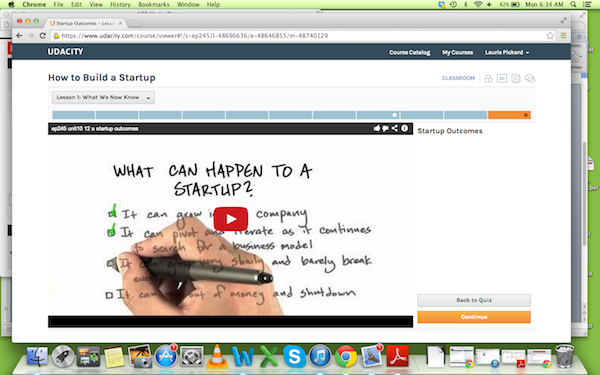

As I’ve mentioned previously, this semester I’m focusing on finance and entrepreneurship. To kick off the entrepreneurship piece, I’m taking a course from Udacity called How to Build a Startup. It is a fantastic course. First of all, Udacity is different from other platforms both in terms of the format and the concept behind it. All of Udacity’s courses are self-paced. In my course, each unit is made up of a series of very short videos – around 2 to 3 minutes. I don’t have much time to do coursework during the work week, but sometimes with this course I tell myself I’ll just watch a couple of videos and then end up finishing a unit because the videos are so quick and engaging.

The other thing I love about Udacity is that all of the courses are focused on acquiring practical skills. Courses are exclusively in the fields of science, technology, math, and business – many are in computer programming. How to Build a Startup avoids all of my pet peeves about MOOCs - the instructor never asksus to post on discussion forums just for the sake of posting, he urges us constantly to get out of the building and test our hypotheses on potential customers, and he goes into detail rather than just skimming the surface of the topics he’s covering.

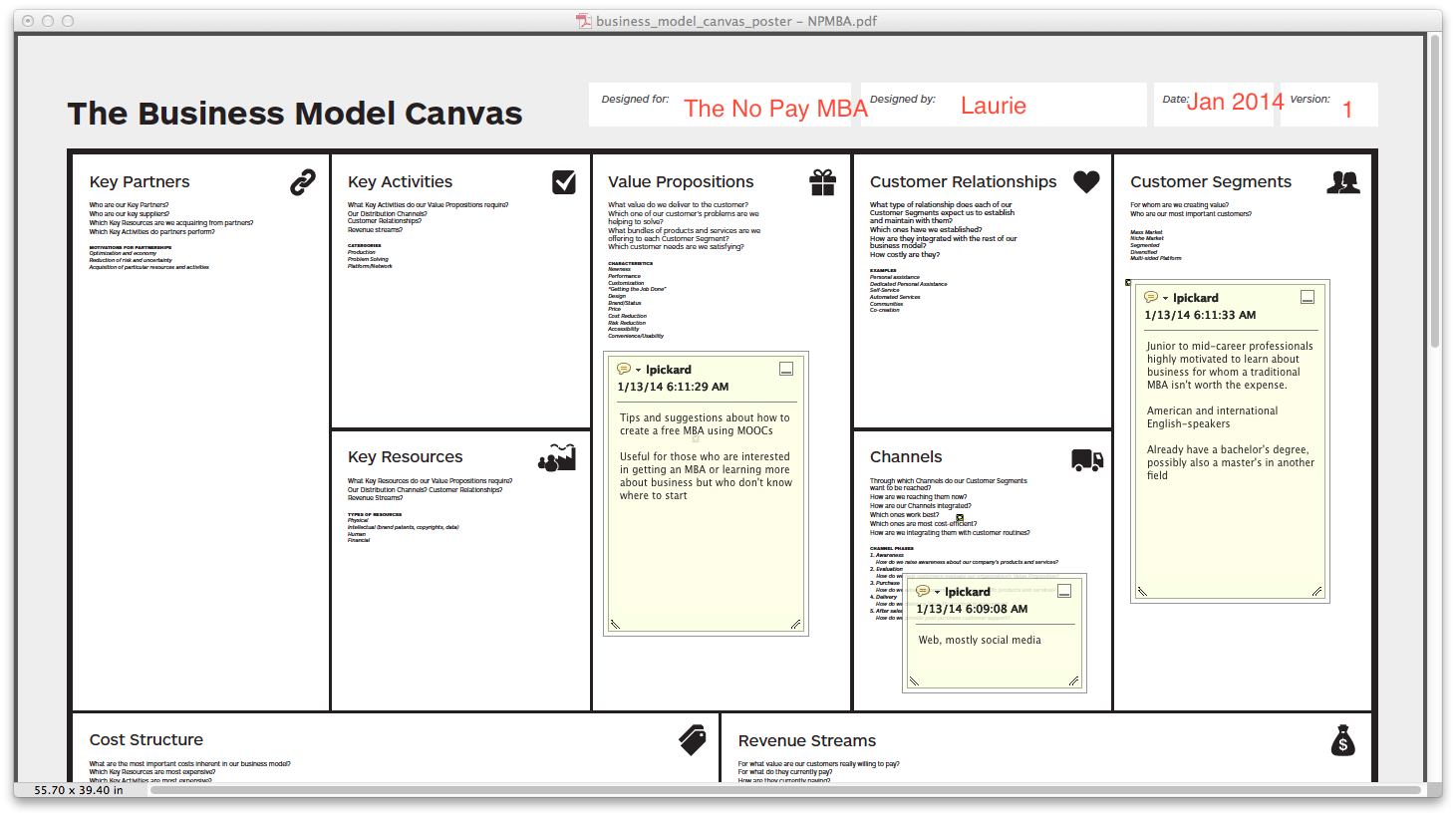

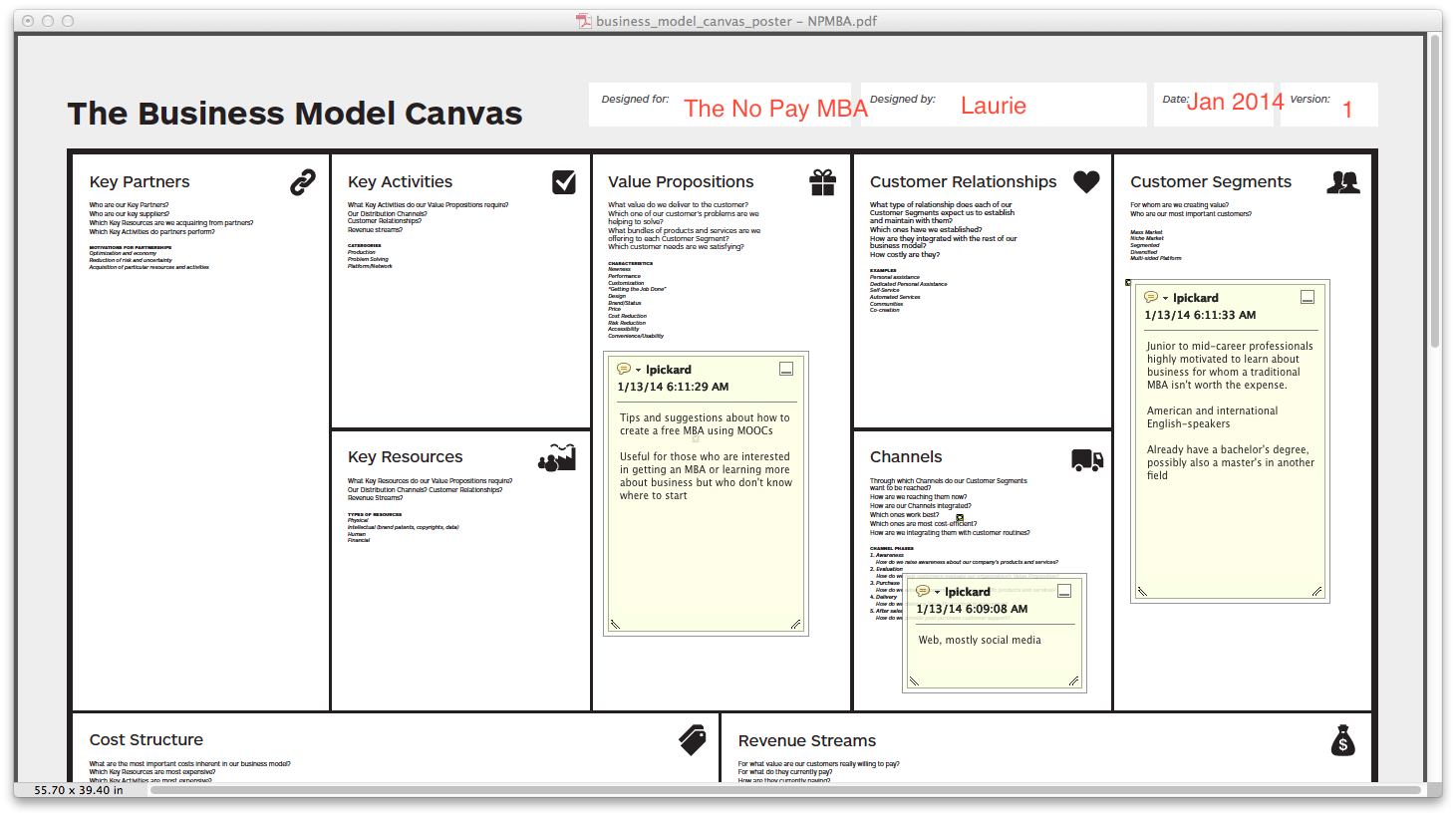

The backbone of How to Build a Startup is something called the Business Model Canvas. This is a great tool for organizing your thinking around a startup business. The instructor, Steve Blank, who has founded many startups, emphasizes that filling in the spaces on the canvas is an iterative process that must involve talking to potential customers. I’m only three units into the course, but I’ve already started thinking about several business ideas. The most tangible so far relates to my current project, The No Pay MBA. Since starting this course, I’ve been thinking in a new way about the value proposition my blog offers to my readers (a.k.a. my customers). I’d love to see this blog become a sort a community hub for people who are working on their own free MOOC-based MBAs.

Below is a partially filled in first iteration of my business model canvas. You can click on it to see a larger version. I’d love to hear from you about what needs those of you who are contemplating doing a No Pay MBA would like to have addressed, what uncertainties or challenges or annoyances you’ve experienced so far if you’ve already started one.

by Laurie Pickard | Dec 8, 2013 | Courses, Platforms, and Profs, Thoughts on Higher Ed and Life

A recent Huffington Post blog entry asks the question, how do you define a MOOC? For example, how big does a course have to be to be considered “massive”? Does a course have to be completely free to be considered “open”? And what exactly is a “course” anyway? For example, does a podcasted lecture count as a course?

I am not overly concerned about whether my coursework falls into the MOOC genre. Rather, what matters to me is that my courses be free or nearly free, that they cover subjects that are MBA-relevant, and that they allow me the opportunity achieve mastery in a subject area.

I’ve taken several different types of free courses since I started this project. My first was a class on coffee price risk management offered by the World Bank. It wasn’t technically a MOOC because it wasn’t open – I needed a CD with an access code to take it – but it was similar to a MOOC in that I was responsible for supplying the motivation to get through the course, and there was no teacher to help me out if I got stuck. I’ve since taken courses on iTunesU, Coursera, Canvas Network, and Open Yale.

Based on that diversity of coursework, here are my criteria for what makes a good MOOC. (Bear in mind that I’m using the term “MOOC” loosely.)

- The course should be intended for an online audience.

It has been much easier for me to learn in courses that are actually intended for an audience that is not physically in the same room as the teacher. While it’s cool to be able to listen in on the regular live classes of top professors, it’s difficult to truly follow along when you’re missing so much of the face-to-face interaction of the classroom. This turns out not to be a problem in a course where the professor is speaking to online students.

2. A course that follows a defined schedule is better than a self-paced course.

I’ve taken courses with a set schedule and deadlines for homework assignments and exams. These courses are much easier to finish than those that require the student to pace themselves for the whole course. That said, flexibility is also a virtue. It’s best when the course offers a window of about two weeks to complete an assignment. That way a heavy week at work won’t totally throw you off track.

3. A simple layout is best.

I’ve taken most of my courses so far on Coursera, primarily because the offerings are so much better than any competitor’s. But now that I’ve started a course on a another site – Canvas Network – I must say I have a strong preference for Coursera’s layout. The side bar on the course home page shows me everything I want to see – links to video lectures, homework assignments, the course syllabus, and the discussion forum all in one place. Canvas walks you through the course, from one module to the next, with the quizzes and discussion forums threaded through. Unfortunately, this system makes it much more complicated to find anything. I recently discovered a series of homework assignments I had missed because I hadn’t correctly navigated the course modules.

4. Multiple forms of information delivery can be effective.

Coursera courses are based around video lectures, often with Power Point slide shows worked through. Canvas uses more text pages, with some live (and later archived) video discussions. The World Bank coffee course I took was almost all text. Some courses have included links to external sites – whether to provide supplemental information, real-world examples, or practice with concepts. All of these forms of delivering information are effective. My Accounting teacher went above and beyond by including animated virtual students in his video lectures, but that’s really not necessary.

5. Don’t just give an overview; go into detail.

I don’t know if it’s that they didn’t have the time to do a thorough job or if they think online students won’t get it, but some of my courses have been too superficial. The main culprits here are International Organizations Management and, as I’m coming to find out, Project Management Skills for All Careers. It really irks me when the professors allude to a skill set that is necessary in the subject they are teaching, then gloss over the technicalities of employing that skill set. For example, my Project Management class recently had a module explaining the importance of making the business case for a new project, but didn’t go into any specifics about how to do the analysis, or how to present the results!

6. Make the homework difficult.

My biggest pet peeve is when instructors assign posting to the discussion forum as homework. The forum gets so crowded with useless posts. “I agree with what So-and-so said.” Or, “Thank you, professor, for an interesting lecture.” You scroll through hundreds of these comments, only to post your own superfluous message and get “credit” for it. Another pet peeve is easy quizzes. If I can ace the quiz without listening to the lecture, it needs to be more difficult. Problem sets are the best kind of homework. Preferably difficult ones. Kudos to my professors of Accounting and Operations Management for making good problem sets and hard quizzes.

In summary, a good MOOC is one that is simple to navigate, that works within the limitations of an online platform, and that is challenging enough to be rewarding.

In other words, give me what I need to succeed, then make me work for it.

My Accounting course is a great example in this regard. Sure, it was difficult, but in the end almost 10,000 of us will be receiving a Statement of Accomplishment. And for this course, I’m truly proud to have earned it.